-

Everything I needed to know about parenting two under 2.5, I learned from amateur theatre

Do you suffer from too much spare time, sleep or personal dignity? Then amdram and/or babies-and-toddlers might be for you!

Here are some things I’ve learned:

Photo by Kyle Head on Unsplash - You need a tip-of-the-tongue repertoire of approx. 80-100 extremely stupid songs, preferably with hand actions and BIG energy. No, bigger than that! Bigger than THAT! OK, now AGAIN!

- AGAIIIIN!

- Qualities required in a toddler/infant mum are basically the same as those required in a good stage manager: co-ordinating several different complex sets of timing while also in the presence of loud music, flashing lights and many trip hazards; ability to shut down

muppets creating chaosoverly-exuberant playfulness without actually causing tears, and a sixth sense for what might be happening in the gap that’s juuuuuust concealed from view by that cupboard door.- I imagine that parenting older kids is probably more like being a director — you can tell them how to speak and act til you’re blue in the face, but no guarantees they’ll actually do it on the night — and being a parent of adults is probably more like being a playwright. But am going to have to defer to other people’s experience or wait and see .

- When it comes to winning over an audience, subtlety is for losers. This has been taken to extremes in my one-woman Gruffalo, performed nightly in our living room. Five out of five sippy-cups from Squirrel, who swears that it spits all over Imelda Staunton’s audiobook version. Otter prefers my intimate spoken-word Round and Round The Garden, but each to their own.

- More song again? Please?

- SOOOOOONG!

- There is definitely no such thing in the world as too much Monster Energy Drink. Until there is.

- Every so often, someone will throw up, have a nosebleed or spill something that they really shouldn’t have been drinking there. Hope and pray that it happens on one of the cheaper costumes and have your wet facecloths at the ready.

- The bit where everyone is standing in the spotlight getting applauded and smiling is only about 1% of the total experience. The rest of it involves helping others get dressed at top speed in the dark, reading the same lines over and over until they’re burned into your Oh help, oh no BRAAAAIN, and struggling to realise the vision of someone who has very specific ideas about blocking, the Stanislavsky method, or why lunch should be composed entirely of string cheese and Ribena.

- There will always be some smart alec in the audience who has put in 0% of the work but has 100% of the opinions. Moooooost of the time it’s safe to ignore them, but occasionally we do need to take on feedback from other human beings or we end up playing nursery rhymes on the recorder in a paddling pool full of baked beans at 10am on the Royal Mile.

- No matter how daunting it seems at the cast announcement, you will eventually grow into the role.

- Man, it’s Show Week. Only a colossal knob would say “Enjoy every moment” because that’s not how this works, but… as much as it’s draining your wallet, your patience and occasionally your will to live, there’s very little of this that you won’t look back on with affection, and one day long for just one more post-rehearsal pub session or one more curtain call.

- Seriously though, watch out for the vomiting. And on no account let them throw the cast party at your place.

- More Gwuffalo again please?

-

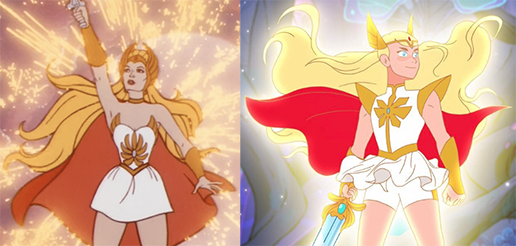

On plastic swords, She-Ra, 70s Bowie and gender

A few weeks ago Squirrel (2.5) was playing at a local playground. Somewhere between the Big Slide and the Wobbly Bridge, she ran across a temporarily-abandoned plastic toy sword. She had an instant Sword-in-the-Stone moment, grasping it by the pommel and hoisting it aloft:

Unrelated: Will Squirrel and Otter be watching the 2010s She-Ra reboot when they’re old enough? Yes. Yes they will. The first thought that went through my mind when I saw this was, naturally enough for an Xennial,”She-Ra!”. I wish I’d managed to get a photo, but having your arms full of wailing 10-week-old while your toddler is literally running amok with a sword will push “capture the Kodak moment” right to the bottom of your agenda, unfortunately.

I looked around for the true owner of the blade, and after asking several groups of kids, found that it belonged to a group of masculine-presenting kids* playing on the other side of the playground. They very kindly agreed that Squirrel could play with their sword, “as long as he gives it back and doesn’t break it“.

* Interesting that I in turn made my assumptions about those kids’ gender, and didn’t think to question them until just now.

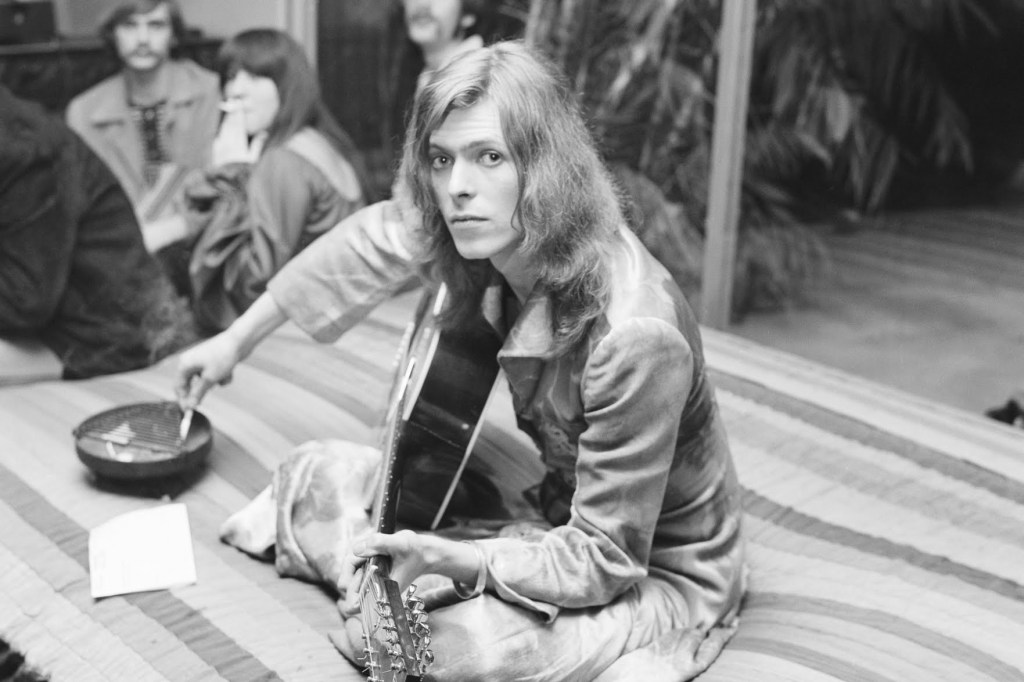

Now Squirrel, it has to be said, is currently a dead toddler ringer for very early-70s-era David Bowie. Medium-height, slight kid with a shoulder-length mop of honey-blonde hair that somehow magically unbrushes itself whenever her mum’s back is turned for five minutes.

She’s usually dressed in a lot of dark denim, blues and reds because I am a deeply lazy human being who hates doing laundy and whose kids are attracted to mud like Boris Johnson is attracted to dodgy dinner parties. And to those kids in the park that day, clearly she didn’t read as “She-Ra”. Instead, she was King Arthur, pulling the sword out of the stone.

It’s definitely not the first time she has been mistaken for a boy, and it doesn’t offend me in the slightest. In fact, having people call Squirrel and/or Otter “him”, or the nice older woman who complimented me on my “lovely little boys”, always makes me vaguely happy, and that is an odd set of feelings in itself. There’s probably some internalised misogyny in there — the part of me that thinks high femme and frills is less-than, weak and pointless and silly, the part of me that spent an entire afternoon as an 8-year-old sitting with my best friend melting the pink crayons out of her crayon box with a magnifying glass so that we could prove we were “proper tomboys” (in retrospect, how fucked-up is that?).

And yet I can’t help but wonder if her current gender presentation makes a difference to the way she experiences the world, and whether that will change as she grows older — if she decides for herself at some point that she wants to wear skirts and sparkles, how will the world feel different to her?

I remember her being very tiny, in between the lockdowns last year, only just starting to walk. One day she stole a football belonging to some nice teenagers in another local park. They grinned at one another and said “Aww, let him have a kick”, and she charged happily around their ankles for a few minutes. Would they have done that if she’d been wearing powder-pink and kittens instead of a navy blue coverall? There’s no way to know.

What doors close and open for a child based on how strangers perceive their gender?

Similarly, on the few occasions that Squirrel had interacted with babysitters and nursery workers (who obviously have known her assigned gender) I’ve noticed subtle, probably unconscious, attempts to direct her play — for example, seeing her scrabbling in a sandpit and encouraging her to pretend she’s making a cake, rather than building an earthwork or digging for pirate gold. Such tiny, unimportant interactions, yet they all add up. We might think that kids have no concept of gender yet, that all these worries and concepts are above their heads, but actually they’re thinking and puzzling and trying to make sense of it all the time.

Of course when Squirrel and Otter get to the ages where they can express a preference for themselves about these things we’ll honour those preferences (as far as possible without physically hampering them, at least — in my past life volunteering with children I’ve cared for girls who were unable to run and play properly because of flimsy, slippy-slidey sandals or constricting skirts, and it’s not what I want for my kids). In many ways I’ll be grateful when their preferences start to be expressed, because if they’re the ones choosing either femme or masculine presentation, I’ll at least know they’re actually getting what they want. But in the meantime it’s terrifying — I was prepared for the responsibility of choosing a name for a whole other person, picking their reading material and the things they would have opportunities to do for the first few years, but nobody warned me that at least until they’re able to express their own preferences, you’re in charge of choosing someone else’s gender identity too!

It’s almost certainly one of the things I’m getting at least slightly wrong, so I guess all I can do is approach it in a spirit of humility and prepare to adjust course as needed. In the meantime, my daughter is running amok on the playground with a borrowed plastic sword, full of the power of Greyskull and a toddler’s outsize joy. I wish she could always have this much freedom.

-

Dear Bette Midler: My body parts are not free on demand!

So, public commentary around the formula shortage in the US. This was always something I was going to have Opinions and Feelings about. But I’m particularly riled up to see this tweet from Bette Midler, someone I’ve previously thought of as someone I’d like if I met her socially:

Disclaimer: If your first thoughts on reading this are “Isn’t formula bad for babies/not as good as breastmilk?” or “But what about the terrible history of formula companies promoting their products in the developing world in the 20thC?”, those are valid questions to ask, but I will need to engage with them another day and in another post.

For now, let’s just go with the assumption that there are as many different reasons why people might choose formula-feeding or breastfeeding/chestfeeding as there are human beings on the planet (and that’s not to mention combi-feeding and exclusive pumping! Hi to all my fellow awkward misfit toys out there!). Leaving aside the fact that OF COURSE I support people making their own decisions about their bodies, I want to do a quick breakdown of my personal angle on why “urrrr why not just breastfeed?” is an appallingly ignorant take on this issue. The fact is that despite the narrative we are often fed of breastfeeding being “natural and free”, many people who would like to breastfeed/chestfeed physically cannot (this was me with my first child), while for others some formula supplementation is what makes it possible to safely breastfeed (this is currently me with my younger child).

My first kid, Squirrel (now 2.5) had a frightening and dramatic birth and early feeding history which I’m not going to go into today — it’s another blog post, or series of posts, which I’m still in the process of planning and drafting. Take home summary: Breastfeeding went to shit, 5-day-old baby went to hospital, we ended up doing exclusive pumping (with some formula supplementation) for 14 months. Incidentally, just in case you’ve ever thought to yourself “Gee, I wonder what it’s like to jam your boobs into a plastic squeezing machine every three hours for a year?”, it isn’t a life I’d wish on my worst enemy, my high school bully, or even those people who keep phoning everyone up about car accidents they weren’t actually in. Thankfully Squirrel is now the world’s happiest and most rambunctious toddler, so all’s ultimately well.

What I will say is that with baby Otter, who is just about to turn 12 weeks old, I am right now basically a caricature of someone who has every possible breastfeeding advantage:

1. Annoyingly middle-class older mum who is economically privileged to have access to a year’s worth of maternity leave.

2. Further economically privileged to have been able to spend vaguely silly money on in-home professional assistance to establish breastfeeding this time around.

3. Highly supportive partner able to assist with more than their share of household duties while I’m feeding Otter.

4. Currently direct-nursing 8 times per day (~3am, ~7am, ~9am, ~midday, ~3pm, ~6pm, ~9pm, ~11pm) — which is another marker of privilege in that I have the levels of mental and physical heath to be able to sustain this.

5. Further physically privileged in that Otter’s birth was very straightforward compared to her sister’s and happened with minimal intervention, which can have an impact on lactogenesis and milk production.

And even with all these advantages, guess what… I am still supplementing with formula. On top of her eight nursing sessions round the clock, Otter also gets ~250ml of the evil science milk throughout the course of the day.

And she bloody-well needs it. You can tell this because even with the top-ups she is still gradually descending through the centiles (ie. her growth is still slower than one would expect to see) — from just over 50th centile at birth to just over 25th now. This isn’t the dramatic fall that Squirrel had; her growth is being monitored, and her GP and health visitor have signed off on the formula supplementation plan. Nevertheless it’s still a source of worry, and pretty good evidence that I’m not quite keeping up with her needs unaided.

I am totally thrilled that breastfeeding is at least somewhat functional this time around, and that I’m mostly feeding Otter directly rather than pumping around the clock like I did with Squirrel. But my point here is that even with all these advantages, without access to clean, safe formula my younger daughter would likely be starving right now. Not in the hyperbolic sense of “she would be very hungry”, but in the actual “her body and brain would be at risk of sustaining permanent damage” sense. Sadly, it does happen (warning for infant harm and death discussed at the link). And we are not the only family in this situation — low milk supply is something that the “breast is best” crew like to downplay and even gaslight women like me about (I have experienced this) but it is a real thing. Plus of course as this tweet points out, once the decision to formula feed has been made months or even years ago, one can’t simply reverse it because a shortage is now occurring:

I can imagine a little of what the parents in the US who are currently struggling to deal with the formula shortage must be going through, having experienced a few empty shop shelves during the first lockdown in 2020 (not to mention the spectacle of scalpers on a certain site named after a river in South America selling £8 boxes of formula for double and triple the price!). Uncertainty about the ongoing supply of safe formula during the pandemic was certainly a factor in my decision to keep exclusive-pumping for as long as I did. And to sneer at formula-feeding parents — who are right now living in fear of not being able to feed their babies — that they should have made a different choice is both incredibly heartless and a great way to demonstrate that you’re ignorant of the nuances of how infant feeding works both physiologically and socially/culturally.

The implication that breastfeeding is “free” is also pretty laughable given the list of economic resources I’ve cited above which were necessary to make even partial breastfeeding happen for me — if I needed to be doing paid work right now, there would be no way I could sink upwards of six hours per day into just feeding, not to mention the spending on lactation support, shortcuts such as prepared food for the adults in the house so I can nurse instead of cook, etc. And we won’t even go into the fact that I’ve spent at least a modest skiing holiday’s worth of money on the collection of manual, electronic and wearable pumps I’ve amassed since Squirrel’s feeding drama! Finally, while I might be happy and privileged to offer my kid nursing whenever she needs it, that doesn’t mean that the milk is necessarily there, which puts paid to the “on-demand” side of the argument too.

So yeah, Ms. Midler, I’m pretty confident that I can say I have “tried breastfeeding”. Why don’t you try having some understanding and compassion? I hear those are free and available on demand too.

Further reading:

Why breastfeeding isn’t a solution to the formula shortage — Dr Rebekah Diamond, Columbia University

-

“Empathy isn’t there”

Sometimes I think that it would really help my mood and mental health if I could avoid all media articles along the lines of “Here are all the terrible setbacks that children are suffering as a result of the pandemic, now let’s panic and freak out!”.

Unfortunately, as someone who works in education and has two kids under 2.5, that isn’t always possible. And the latest iteration of this has stung me into wanting to respond. This article appeared in The Guardian on Monday (04/04/2022): Empathy isn’t there: The pandemic effects on children’s social skills.

This is an article “told to” the journalist by “Jemma”, who is a nursery school teacher in West Sussex. Jemma freely unloads on all the shortcomings she perceives in children who (if they are entering nursery for the first time this school year) have likely spent the majority of their lives under lockdown. I think it’s quite sensationalised, and also a very good example of the kind of catastrophising I’m alluding to above.

Opening disclaimer: Yes, I am defensive as hell about pandemic parenting, and the fact that many of us have been through some really difficult and stressful experiences over the past two years. I don’t want to detract in any way from the fact that early years teachers and nursery staff have been through all sorts of challenges too, or that their difficulties are likely to be ongoing throughout the next few years.

That said, here are some of my responses to Jemma’s thoughts:

If children have siblings and they’ve mixed with others, they tend to be on the same level socially as before the pandemic. But the ones who are only children and have just been in the household with mum and dad don’t know how to interact.

At the risk of sounding like I’m missing something… yes, and? In other news, water wet, sky blue, people who have had little experience with a setting or situation haven’t learned the rules for interacting in it yet?

They have issues with sharing, being very overexcited and turn-taking. They’re quite advanced in numbers and letters for their age because they’ve been at home with adults, or they’ve been playing a lot on tablets, but they are very behind socially, the empathy isn’t there.

Being unaccustomed to sharing/taking turns with a large group of peers and “being very excited” (about attending what is presumably still a very new setting for these kids) is NOT the same thing as lacking in empathy, and it’s unnecessarily alarmist to state that it is.

If Jemma, or you, or I, were to be dropped down in a completely unfamiliar social setting — let’s say, a 16th-century Japanese tea ceremony, or a 17th-century European court masque, or a drag ball in 1980s New York — there is every likelihood that we would not know the right ritualised responses and behaviours, would make total arses of ourselves, and would quite likely even end up offending or hurting someone. People in that setting would probably think we were semi-feral unsocialised oafs if we were lucky. But would that make us “lacking in empathy”?

In many ways, a nursery school classroom is an equally ritualised space — how can a kid who’s never been in a group of more than two or three other children before possibly fathom what “line up nicely” or “circle time” might mean? While I understand that children have now had since September to internalise these lessons (I’m writing at the beginning of April), it seems very perverse to me to claim surprise that they are being slower than previous cohorts to do so, let alone to argue that this slowness says something about them as human beings.

If Jemma were reporting a gang of pandemic toddlers going around deliberately hurting one another, perpetuating petty cruelty to animals or setting small fires (which is what the heading of the article makes it sound a bit like!), I might be prepared to accept that there’s a problem here. But not sharing toys and getting over-excited? That sounds like normal little-kid behaviour that’s been a bit exacerbated by lack of experience with large groups of other children, not a generation of empathy-less mini-serial killers!

It’s not a criticism of the parents because they were forced into that situation, but you can see it in the children’s social skills. Under five, social skills are everything, it’s the marker of how they will develop more than whether they can say the alphabet or count to 10. Children with good social skills and interaction, even if they’re not the quickest at learning to read or write, often have the best educational outcomes.

The link between social skills and academic attainment here is a funny one. While yes, there is a known correlation between the development of self-regulation skills and academic performance, I went to Oxford and hoo boy, I could tell you some stories about a parade of seriously brilliant and high-achieving people for whom “social skills are everything” was definitely not the case. (Full disclosure: I strongly suspect I might be the subject of some other people’s stories, too!).

Additionally, if the children who are suffering from slower social development are “quite advanced in numbers and letters” as Jemma claims in the previous quote, could we not put our energy into advocating to retool the Early Years curriculum to spend more time on the areas in which they’re showing deficits rather than catastrophising about empathy-less children? I suppose “We need to rewrite our lesson plans: The pandemic’s effect on EYFS curriculum design” wouldn’t be as attention-grabbing a headline, but it might be a more constructive way to approach the problem.

Also, I don’t know about you, but personally I tend to find that anything that phrases itself as “not a criticism of the _____” is usually exactly the opposite — it’s one step up from using “no judgement” as a quick preface to an extreme attack of Judgey McJudgefacing in my experience. The non-criticism here definitely still seems to convey that those parents who have worked from home with their kids are in the wrong, especially as elsewhere the article points a specific finger at “slightly more middle-class children [who are] more likely to be only children, have older parents, and their parents are mostly office workers…. A lot of children were put on tablets.” I’d really like to see concrete evidence for this group as being more or less disadvantaged than others, as most of the other preliminary research I’ve seen so far has pointed in the opposite direction (ie. that developmental delays in the pandemic have been correlated with socioeconomic disadvantage).

The parents are definitely making it worse for their children socially and for themselves. We’ve got one particular little boy, he’s four and he’s not ever mixed with children at all. The mum is extremely nervous about Covid and so over-anxious that as soon as he cries, she’ll keep him off because she thinks he’s been traumatised. He’s a completely normal boy but he’s not being given a chance because her anxiety is transferring on to him.

More not-at-all-criticism of the kids’ parents here, I see 🙂 Actually, Jemma and I are kind of on the same page with this anecdote — if what she describes is accurate, it does sound as though a combination of circumstances have set this kid up for having some very bad experiences with nursery school, and that sucks.

In an ideal world, the nursery school staff would work with this parent to try to improve her son’s experiences and alleviate her anxiety as much as possible. She sounds like she might have had some traumatic experiences during the pandemic, and is probably having a horrible time right now if she believes that sending her child to nursery is traumatising him, whether that belief is accurate or not. Unfortunately we live in the world where instead of that work happening, the nursery school staff member turns around and publishes her complaints about the poor woman in a national newspaper.

“Empathy isn’t there” in Jemma’s classroom, but I’m not convinced that the kids are the ones who are missing it.

Dans ses écrits, un sage Italien

Dit que le mieux est l’ennemi du bien.

– Voltaire